03/05/2017

By Paolo Pane

Having read the drafts of the novel by Raffaele Lauro, “Don Alfonso 1890 - Salvatore di Giacomo and Sant’Agata sui Due Golfi” has allowed me to reflect on the extraordinary contribution of “pioneer” restaurateurs and hoteliers to the origin and development of tourist economy of the Sorrento Coast, with the centre of gravity in Sorrento, from the end of the eighteenth century to the first half of the nineteenth century, from the second half of the nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century, and from after WWII until today. From the tourism of young aristocrats of the Grand Tour, predominantly individual, to that of the first noble and then economic elite, until the explosion from the end of World War II onward as a mass phenomenon in its economic and social components: from tourism aristocracy to tourism democracy. It passes on from the tourist demand of small groups of people and families, distinguished by culture, prestige and wealth, to the collective demand of entire social classes benefiting from the postwar economic development and the consequent growth of income, organized by tour operators and international and local travel agents. At the same time, the Sorrento and Sorrentine Peninsula tourism offer is growing in terms of goods and services: the historic inns become at first established restaurants of regional cuisine and then true temples of high cuisine such as Don Alfonso 1890. Guest houses, such as Pensione Iaccarino, are transformed into large hotels with all services available for customers, or there are new ones built with state subsidized and Cassa per il Mezzogiorno loans. The structure develops from the founder to the family dynasty across four generations. From this point of view, the stories told in the novel about the Iaccarino dynasty from Sant’Agata sui Due Golfi appear exemplary, almost emblematic, although they are not the only ones: from Don Alfonso Costanzo to his children, from the children to the grandchildren, from the grandchildren to the great-grandchildren. Similarly, other family restaurant dynasties of the Sorrentine Peninsula are also growing and continue to represent today the main business resource and the main shield against criminal infiltrations in our economy. The Author, not only a writer, but also a historian and a politician from Southern Italy, who grew culturally in the continuity of Benedetto Croce’s historical school, along, also as a collaborator, the Southernists, historians and politicians of the likes of Francesco Compagna, Giuseppe Galasso, Ugo La Malfa and Giovanni Spadolini, did not miss however an essential peculiarity: the phenomenon of southern emigration, as well as the emigration of Alfonso Costanzo to America in search of employment, who returns with his savings to start his entrepreneurial venture and make his dream come true. Based on a single, happy and successful story Professor Lauro drew a historical, economic and sociological fresco of strong narrative impact on the general phenomenon of the southern emigration at the turn of the nineteenth and the twentieth century to North and South America, to New York and to Buenos Aires. The emigration of millions of people from Southern Italy becomes a non-secondary component of the Southern Question, today more current than ever. Based on the tragedy of southern emigration, on the hopes, misery, fears, illusions, humiliations, disillusions, sacrifices and pain of millions, I wanted to deepen with him, always available and open to discussion, those historical-political and economic-social issues that burn inside him and that today more than ever affect with endemic unemployment our future of the southern youth.

Q.: It would be interesting to understand the phenomenon of southern emigration between the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, Professor Lauro, starting from the socio-economic picture of Sant’Agata sui Due Golfi and the Sorrentine Peninsula in the nineteenth century in order to extend the analysis to the whole of Southern Italy after national unification.

A.: After the Turkish invasions of the sixteenth century with the kidnapping of hundreds of women and men, and the great epidemics of the seventeenth and eighteenth century which affected the people of Massa Lubrense, the district of Sant’Agata sui Due Golfi, mainly Sorrento and Naples, established itself as a privileged place of residence because of the freshness and salubrity of air, as well as the genuineness of food products. It was inevitable, a slow but constant socio-economic transformation with an impact on old and new work activities. As for the past, for example, the handicraft of knives and scythes disappeared, a flourishing time, as the last masters of the trade had moved to Naples among the alleys and warehouses of Portanova. Silk-processing, as in the whole Sorrento Peninsula, survived in some households in form of preparation of clothes, scarves and ribbons. On the other hand, activities related to land cultivation and, in the summer, to fishing and to trading natural and processed products, in particular in dairy sector, were strengthened. The products were sold in Sorrento and Naples.

Q.: What were these natural and processed products that ended up on the tables of wealthier Sorrentines and Neapolitans, who loved to stay with their families in the summer on the Sant’Agata hill and in the other, just as popular districts of Massa?

A.: First of all, the olive oil of Sant’Agata, the fruit of Sant’Agata (the famous lemon apples, walnuts, lemons and the famous late cherries), cheeses, dairy products (first of all, butter), calf meat, the local game (quail, thrush and warbler) and fresh fish (from anchovies to mullets, from squid to lobsters). Although the products would arrive to Naples under the name of Sorrento: the butter, the “butirro” of Sorrento, was in fact very famous! There was also a local accommodation market: the women from Sant’Agata would rent their guest rooms (quartini) in the summer, including daily services of housekeeping, laundry, shopping and cooking.

Q.: There was, therefore, economic development and not backwardness, as across the South post-unification?

A.: Certainly, the conditions of the Sorrento Coast were not those, i.e. desolate, abusive, tormented as in the deepest South, plagued by unemployment, sickness, hunger, and misery, where workforce was always in the hands of corporals, thugs, passed on with all bits and pieces from the service of baron landowners to the new rich, the Piedmontese Liberals, flourished after the defeat of the Bourbon monarchy. Everything was changed, but everything remained the same, to say it like Pedro Calderón de la Barca: exploitation, misery and unemployment! In terms of Sant’Agata and the Sorrentine Peninsula, despite the qualitative and quantitative evolution of the communities, new work activities did not manage to resolve, especially in winter, the problem of hardly sufficient supplies, generally speaking, to guarantee the survival of families and the dignified existence ensured by family heads for the numerous offspring surviving the often lethal infant illnesses.

Q.: The life conditions in Sant’Agata and in the coast were not as dramatic as in the deeper South?

A.: Certainly not! The unification of the Italian nation and the first industrialization of the North was also done at the expense of the South, aggravating the almost medieval states of atavistic misery and social frustration. The family heads from Massa, Sant’Agata and Sorrento, especially on hills, managed to navigate themselves between farm works, fishing and small construction. When necessary, they became peasants, fishermen, masons, helped by their industrious and tireless wives ready to contribute with occasional work to push the boat forward, to raise their offspring and dream of a better future for them.

Q.: Everything, however, was dominated by precariousness and lack of prospects as we have them at present?

A.: Adverse meteorological conditions, capable of destroying crops, hinder fishing or slow down the food trade with Naples were enough to cause panic among many families from Sant’Agata. Or an uncontrolled epidemic affecting dairy animals that deprived the rising dairy product industry of its main ingredient, milk.

Q.: Did this climate of misery in the South and precarious work on our coastline pave the way for the great exodus of entire southern families, men, women and even children, alone, in search of employment in the “promised land”?

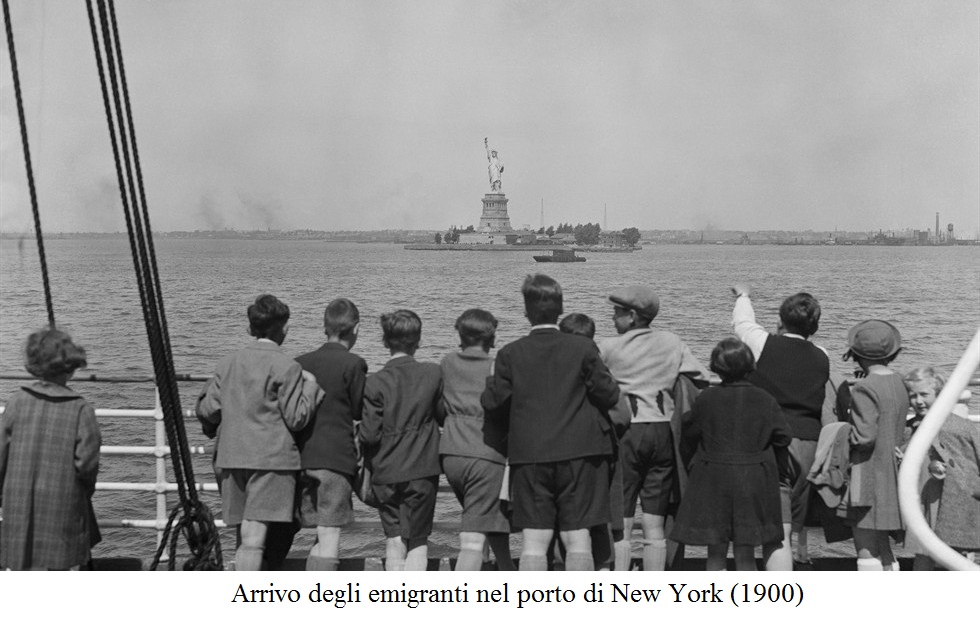

A.: In this climate of hardships, sacrifices and dreams, in Sant’Agata and in all of Campania and Southern Italy, Calabria, Basilicata, Puglia and Sicily, the myth of “La Merica” as the promised land spread and rooted itself, where in a few years, without even knowing the language, semi-illiterate and without a trade, you could accumulate a fortune and after a few years return to your country as a “rich man”, able to buy houses and land to cultivate on your own. The bosses, the masters of that exploitation market, travelled across the countryside to promote the “American paradise”, and to organize for the unconscious southern unemployed their transoceanic voyage on dingy boats, thrown into third class or in the trunk, often prey to deadly epidemic outbreaks due to precarious hygienic conditions, and often victims of shipwrecks. Not to mention what followed next, the true suffering: the entry controls with the anguished look at the Statue of Liberty, the network of bosses on arrival, the true criminal organisation of work for the Southern Italian immigrants, a pallet in a horrible room of a block of flats in Little Italy, the most humiliating, most dangerous and worst paid jobs in major public works in New York.

Q.: Nobody knew what they were facing?

A.: No one could know the human tragedy of arriving to a foreign country to be discriminated against as immigrants, dressed in rags and with a bundle, forced to accept the most humiliating and worst paid jobs, and be subjected to harassment, suffering and unspeakable humiliation. Also because the first southern emigrants in their letters to relatives sent beautiful photos in party outfits, and they looked good while being ashamed, not to worry their parents, wives or children who stayed at home by telling them of their personal struggle, only proud to include dollars earned with so many sacrifices. The fame of those money, in the eyes of the recipients a tangible evidence of the success of emigration adventure, fuelled a massive wave of emigration to the American continent, to the United States of America, Argentina, Brazil and Canada.

Q.: In numerical terms, how many southerners set out in search of fortune?

A.: Not less than four or five million. Many, however, returned disappointed and desperate.

Q: Many did, however, succeed and fit positively in the economic fabric of the new world?

A.: Certainly, but you will need to get to the third generation because in the first decades the competition and rivalry with the Irish affected the economic and social rise of the Italian-Americans.

Q.: Who benefited the most of this mass exodus?

RA: Regardless of individual, physical and moral sacrifices, the southern emigration contributed to resolving the frightening unemployment caused by the underdevelopment of the South, and provoked a breakdown of social equilibrium, putting into crisis the idleness and privileges of the agricultural bourgeoisie, accustomed to exploiting the abundant labour, especially young men. Emigrants’ money favoured mainly the national ruling class, an active balance of international payments, the stability of lira and the industrial investments in the North.

Q: The emigrants’ sacrifices favoured only the industrialisation of the North? And what about the South?

A.: A terrible paradox. The South remained in an impasse, also because of fascist autocracy and the Mussolinian war. In order to address the southern question, we must await the reconstruction and the post-WWII period. With the lights and the shadows we know. More shadows than lights, if the situation today is what you and I know very well.

Q.: Why did young Constanzo Alfonso leave as an emigrant for New York in 1886 at the age of just fourteen?

A.: His father, Luigi, died and he did not want to leave his beloved mother, Rosa, to pull the cart on her own. He left confident with his mother’s uncle Luigi and aunt Carolina’s protective presence in New York, but promised he would come back and he returned after only four years, to start his entrepreneurial venture with the opening of Pensione Iaccarino. His dream came true. That spark of the founder started a hospitality and catering dynasty with children and grandchildren, and with its greatest expression in grandson Don Alfonso Jr., a great master of Mediterranean cuisine and one of the most prestigious chefs in the world.

Q.: All in all, a positive American experience, that of Alfonso Costanzo Iaccarino?

A: More than a mere experience, albeit positive, an epic, a myth, a symbol, whose path fascinated me and inspired me in writing this novel.

[..]

[..]  [..]

[..]  Carissime, Carissimi, desidero ringraziare, di cuore, quanti hanno tempestivamente aderito al mio invito a votare e far votare, nel concorso Rai “Il Borgo dei Borghi”, la [..]

Carissime, Carissimi, desidero ringraziare, di cuore, quanti hanno tempestivamente aderito al mio invito a votare e far votare, nel concorso Rai “Il Borgo dei Borghi”, la [..]  "Paradossalmente le ultime vicende parlamentari sulla delega fiscale e il voto, per un soffio, sul catasto, stanno testimoniando come la complicata emergenza della guerra in Ucraina, piena di [..]

"Paradossalmente le ultime vicende parlamentari sulla delega fiscale e il voto, per un soffio, sul catasto, stanno testimoniando come la complicata emergenza della guerra in Ucraina, piena di [..]